Edition #001 AI for Flood Resilience, The World’s #1 Climate Problem

Read and download Edition #001 below:

Watch the full interview on Youtube:

Welcome to Intelligence Age

Greetings from the bow shock.

If we have a niche, it’s at time’s bow shock — that permanent, collisionless shock-wave as a planet’s magnetosphere faces into the oncoming stellar wind.

This metaphor is, of course, an imagined shock wave in space-time, as our civilization grits its teeth and faces the relentless blast of tachyon particles from the future head-on.

The future we are streaking towards will have ever-increasing complexity, dimensionality, and entropy. Moreover, our means to respond to the pace of change and multiplicity of challenges will push our civilization like never before.

This quickening effect and our very human limitations to respond to it were detailed in the bestselling “Future Shock” by Alvin Toffler and Adelaide Farrell over 50 years ago.

However, respond we must.

Another celebrated futurist, GUI (Graphical User Interface) inventor Alan Kay, once said, “the best way to predict the future is to invent it.” However, before we respond, before we invent it, we need to first understand and imagine the alternate future we want to build.

We are so pleased to share edition #001 of Intelligence Age with you. Inside you’ll find four articles on the topic of flood resilience and AI, derived from a fascinating deep-dive interview with practitioners and colleagues, Biggy Nguyen and Guy Schumann. You can listen to that full interview here.

I hope this edition inspires you to build a more intelligent future.

JAMES PARR

DIRECTOR, FDL

CEO, TRILLIUM TECHNOLOGIES

Credit: Misbahul Aulia/ Unsplash

Floods Are The World’s #1 Climate Problem

When people think of climate change, they think of animal extinction, or catastrophic hurricanes. They think of deadly heat waves and crop-killing draughts. Floods are not often the first phenomena to come to mind. They are slower, and more ubiquitous, affecting everywhere in the world.

Their danger, however, is more insidious than you may imagine. Floods are the most frequent form of natural disaster on Earth and kill more people each year than tornadoes or hurricanes. Extreme flood events cost nearly five billion dollars on average, and around three billion people were affected by floods in the thirty year period between 1980-2009 — likely an underestimate.

Of these three billion, about a million were injured or killed. The rest experienced property damage, financial duress, illness from polluted water, and psychological trauma. Aside from the immediate danger they pose to human life, floods also represent a host of other ill effects. They destroy crops, damage infrastructure, and render large swathes of territory uninsurable. When areas become uninsurable, businesses leave, tourists stop coming, and entire cities experience social decline.

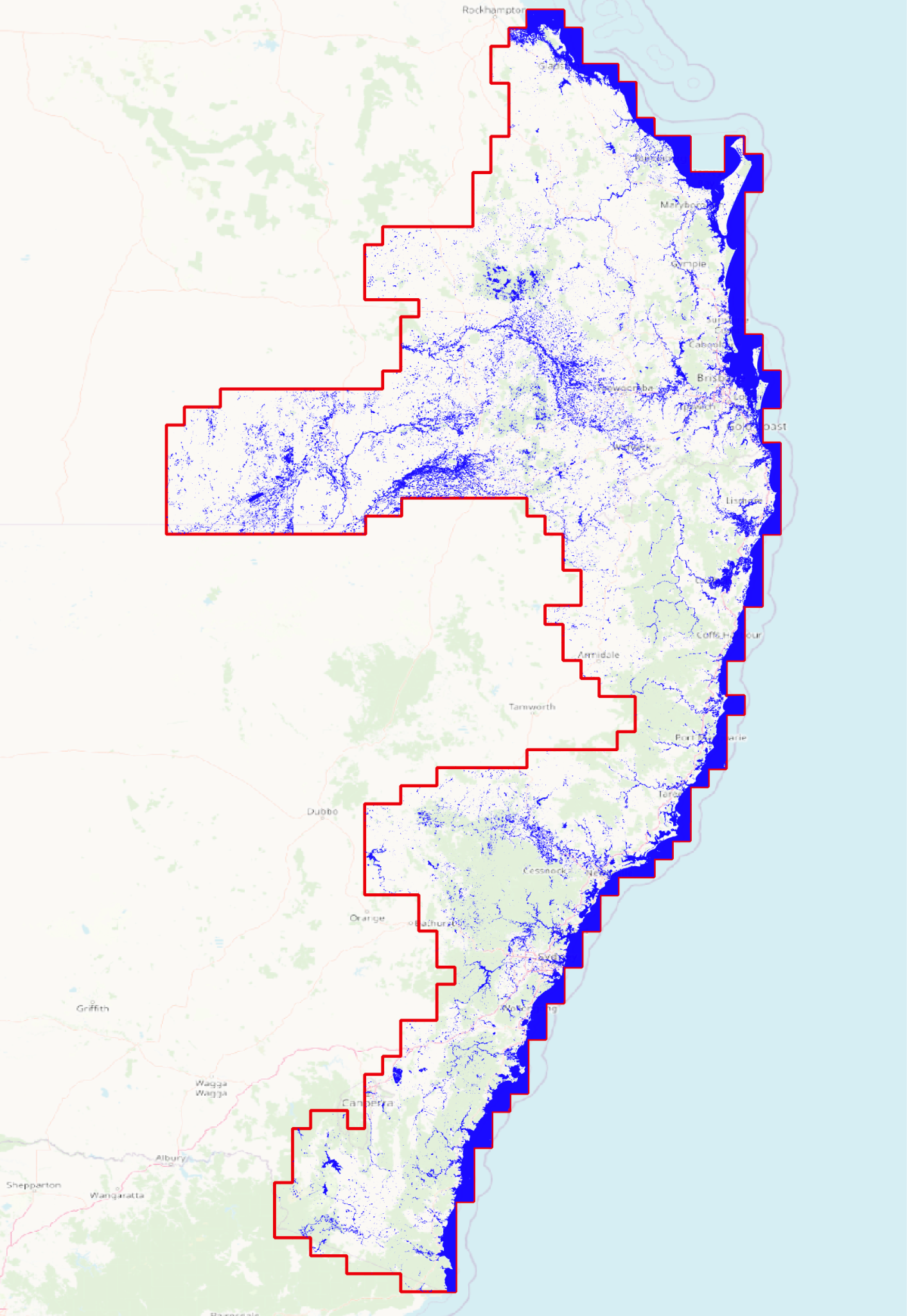

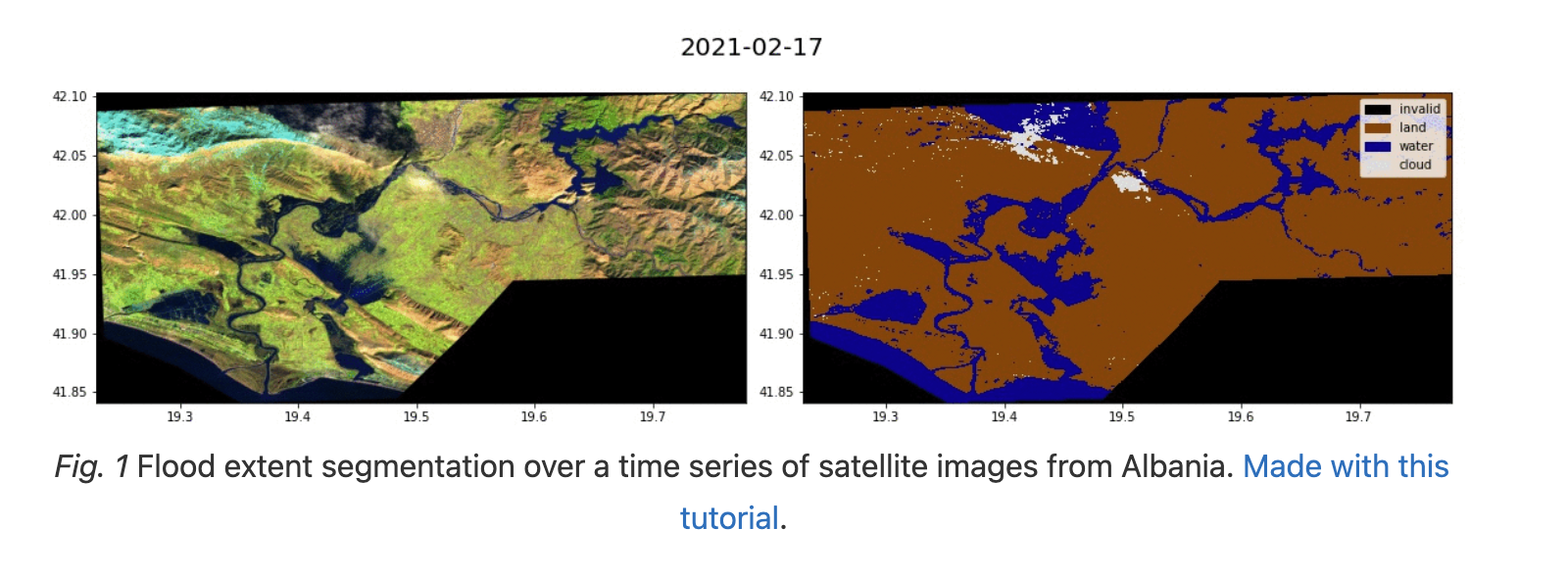

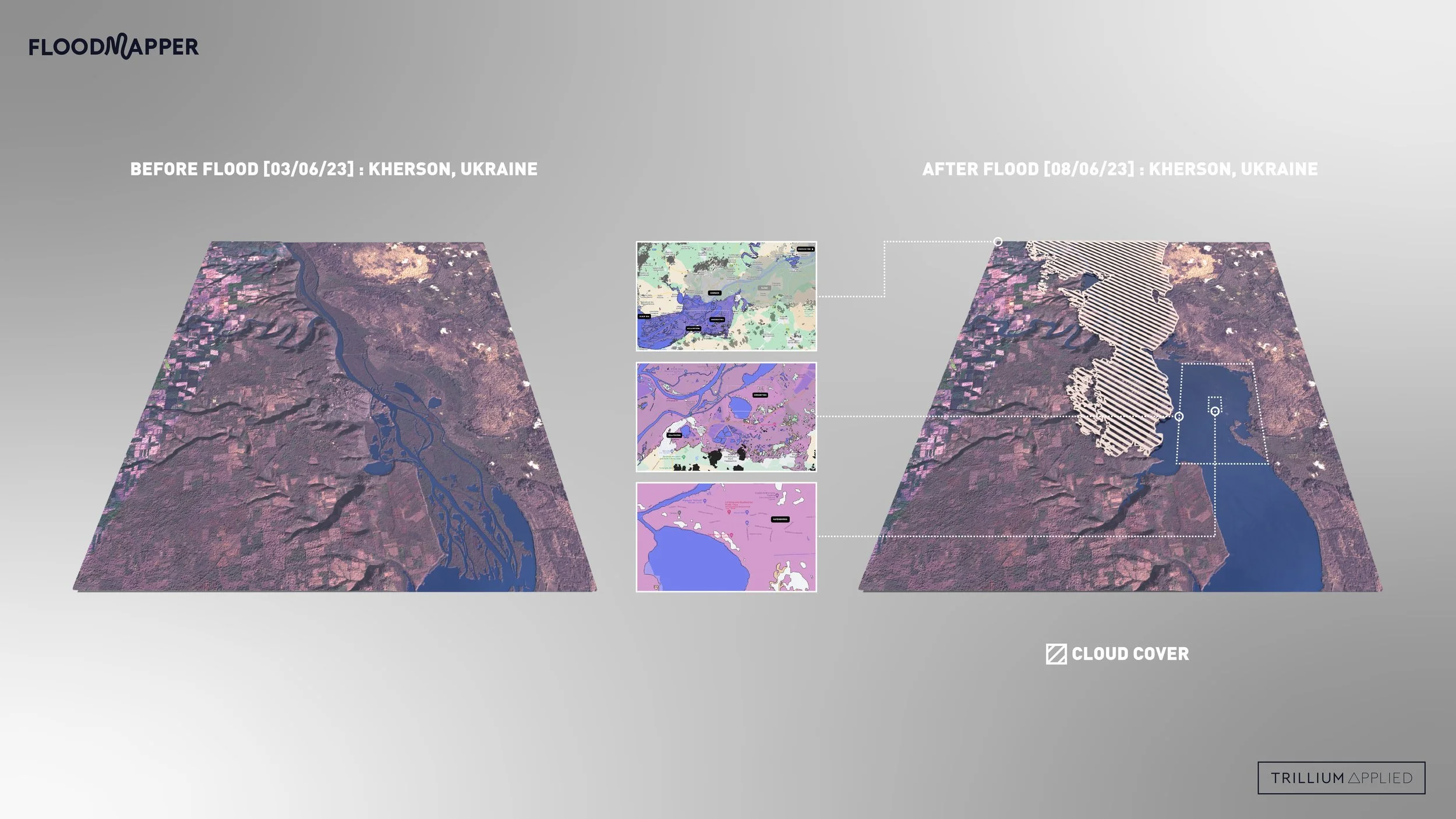

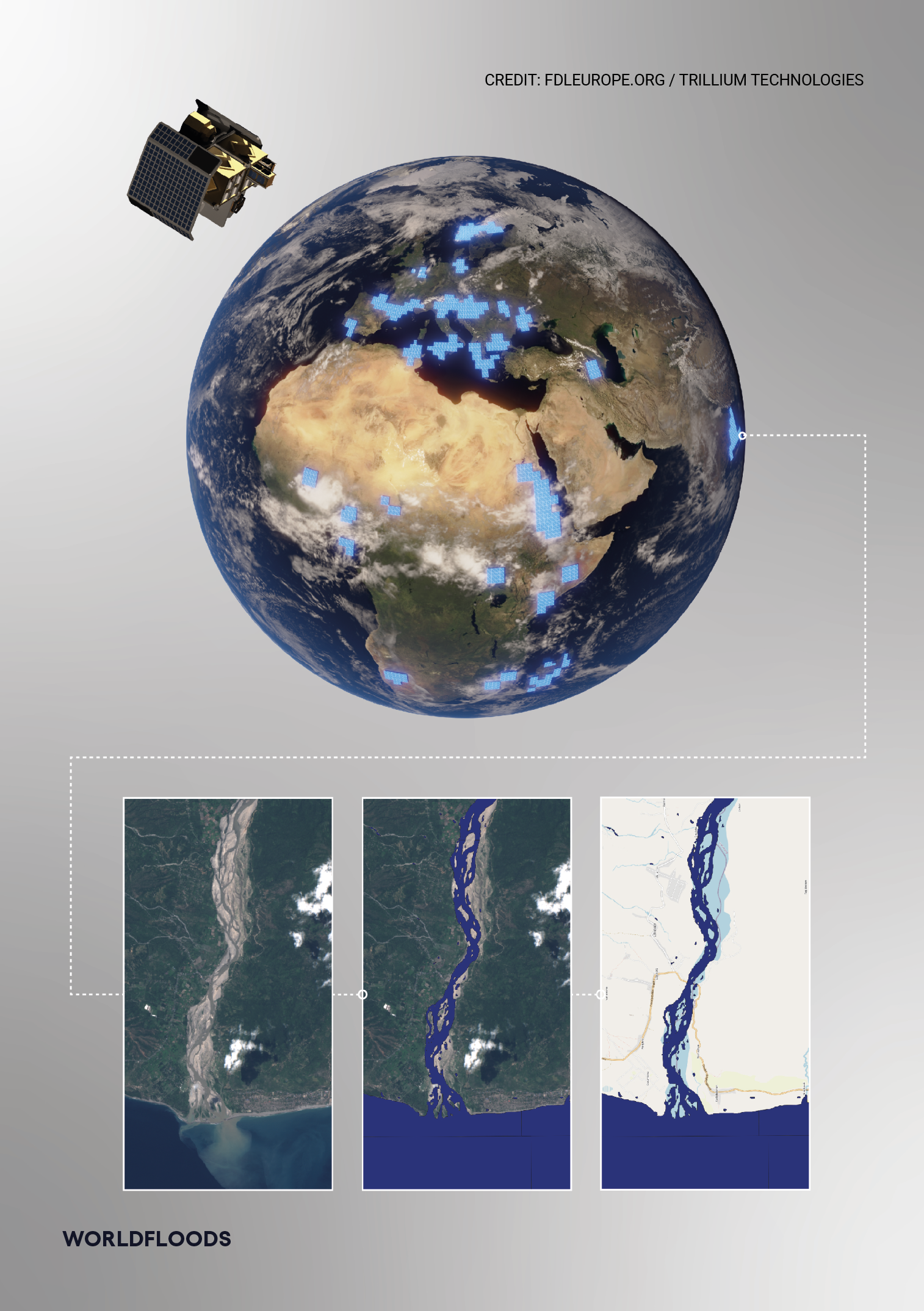

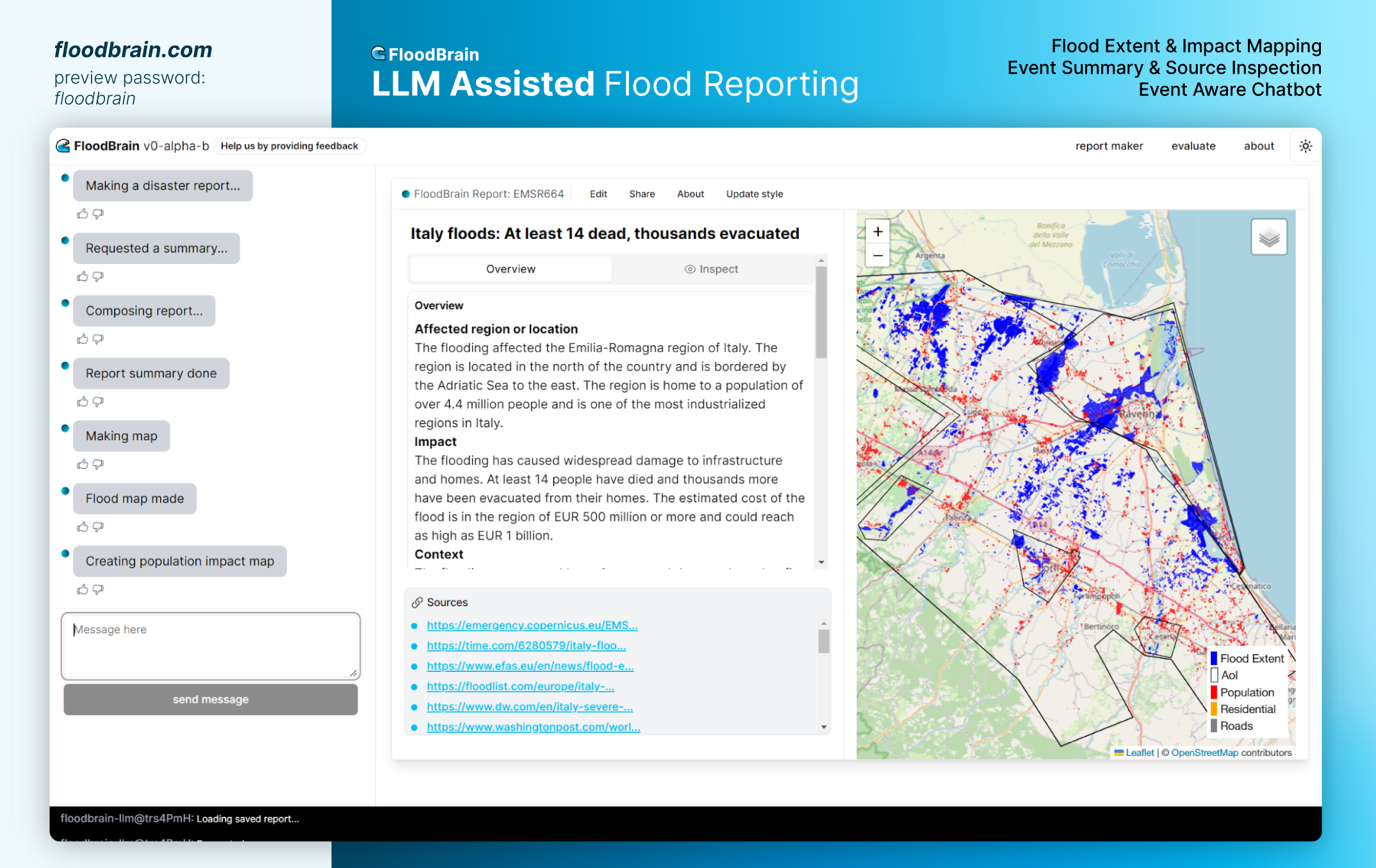

Climate change is here, and it can be seen in the prevalence and magnitude of everyday flooding. AI solutions like FloodMapper and ML4Floods aim to bolster flood resilience by providing technology that helps support flood response measures, especially during the recovery phase.

Contributors

Biggy Nguyen

Biggy Nguyen is a seasoned professional in the finance industry. She brings more than ten years of experience to the table in relationship management, partnership management, and advocacy for trending topics such as resilience and climate change adaptation.

Since 2021, Biggy has been a business development and sales consultant to start-ups and scale-ups. She worked with UBS Switzerland from 2008-2014 and Swiss Re from 2014–2021.

During her tenure at Swiss Re, she served as product owner for a “Disaster Resilience Partnership” initiative in collaboration with Microsoft which aimed to build digital twins for better disaster resilience. Between 2017-2020, she was based in Singapore and developed risk transfer solutions for the public sector in Asia as well as multilateral donors.

She also led the Swiss Re delegation in projects working on grants from the InsuResilience Solutions Fund in Asia. Previously, she managed public-private partnerships with development and humanitarian actors globally that advocated for resilience, climate adaptation, and disaster risk financing.

Biggy holds a bachelor of science in business administration and received her executive masters degree in public administration from the Hertie School of Governance in Berlin, Germany.

Guy Schumann

Dr. Guy Schumann is an internationally recognized senior scientist active in disaster-related projects, primarily focusing on water-related risks. He holds several affiliations in both the U.S. and Europe where he works mostly on European Space Agency (ESA), National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and European Commission-funded projects. He holds visiting academic positions at the University of Bristol and is also an associate at ImageCat, an international risk management innovation company supporting global risk and catastrophe management needs.

He is the founder of RSS-Hydro, a European R&D company active in Earth observation (EO) and computer modeling of water risks. He also regularly participates in Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) innovation projects and is an expert flood consultant for the United Nations World Flood Programme (WFP) and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

Guy holds masters degrees in geography, environmental Science, and remote sensing, and received his Ph.D. in geography from the University of Dundee in Dundee, Scotland.

James Parr

James is Founder of FDL Europe, an applied AI research lab with ESA and Oxford. FDL has successfully demonstrated that structured interdisciplinary problem solving, sprint methodologies, radical collaboration methods and partnering with commercial organisations is a powerful amplifier in applying AI to the science and technology goals of space agencies.

FDL also has a sister lab in partnership with NASA and the SETI Institute. In 2020, an FDL was established in Australia with the Australian space agency tackling bushfires. Over the past five years, FDL has created ML workflows for comet detection, mapping the Moon’s resources, flood prediction, post-disaster damage assessment from space, super-resolution of the Sun’s magnetic field, asteroid shape modeling and co-operative robotics.

James is also founder and CEO of Trillium Technologies - a technology contractor that specialises in the application of emerging technologies to grand challenges, such as climate change, violent extremism, prevention strategies for cancer and obesity, deforestation mitigation, climate resilience and planetary defence from asteroids.

Can (And Should) AI Help Predict Extreme Weather?

2023 has seen some of the hottest days in recorded history, combined with massive floods in India, Chile, Ecuador, Brazil, South Africa, the Northeastern United States, and more. As extreme weather has proliferated, so too have AI capabilities for weather prediction. AI models that can proactively predict extreme weather events have grown in sophistication and maturity in recent years, but while these models are faster and cheaper than traditional weather forecasting systems, they are still far from perfect.

Biggy Nguyen recognizes the potential controversy of using AI for such predictions. “My first thought was: of course you deploy AI. But I can also see the skepticism. What if you release early warning notifications to a village, and that village evacuates and prepares itself and is just mildly affected, whereas a village is hit really hard that wasn’t notified? People will look at the tool with a strong question mark.”

“While current process-based warning systems are also imperfect, at least they come with an individual or institutional scapegoat”, Biggy adds. Their mistakes don’t draw an entire class of technology under suspicion. People — not just individuals but governments and nonprofits — need to maintain trust in AI if it is going to be utilized productively.

An answer, for now, is keeping humans in the loop to interpret AI-based extreme weather forecasts and communicate them to a general audience.“Warnings are tricky”,Guy Schumann says.

“They trigger a lot of actions that are very resource-intensive in terms of people and money. You don’t want to trigger a warning and have your entire fire rescue deploy at a national level — and then nothing is happening.”

Not only does the scientific community often fall short on extreme weather prediction, but there is also a gap in how we effectively communicate those predictions to a general public in a way that inspires action. “People are very aware of what it means if you go to Las Vegas and put money on the table,” Guy says. “They understand that they won’t win and they make careful bets for the most part. And yet when it comes to flooding and extreme weather forecasts, people don’t react consistently to the probability and uncertainty.”

The human psyche is complex and motivated by often-conflicting impulses in its quest for safety. Escape, stay put.

Flee to safety, burrow and hide. Human beings will always question things — this tenet goes beyond flood evacuation warnings to global pandemic policies and other issues of public health, like childhood vaccination.“You will always have people that question things. I don’t think we should not use AI because people are scared of the unknown. There are always things to be scared about. And there’s a lot scarier stuff out there than having an AI model doing extreme weather predictions.”

It is a fact that AI weather prediction has not achieved bulletproof accuracy in its current state. But at the same time, perhaps accuracy matters less than other factors, like speed.

“If you need to get some relevant data right now, accuracy is lower among the list of priorities… I need to be able to see the information in front of me. AI is wonderful because it can give you that information right now.

We need time to make it more consistent and accurate, but it gives you something to work with.”

And traditional models aren’t airtight either.

“We need machine learning because traditional models struggle to get extreme events right,” he says. “We want to have more methods, more models, and if the models we’re using aren’t working, it’s better to try with another model than to give up [on AI].”

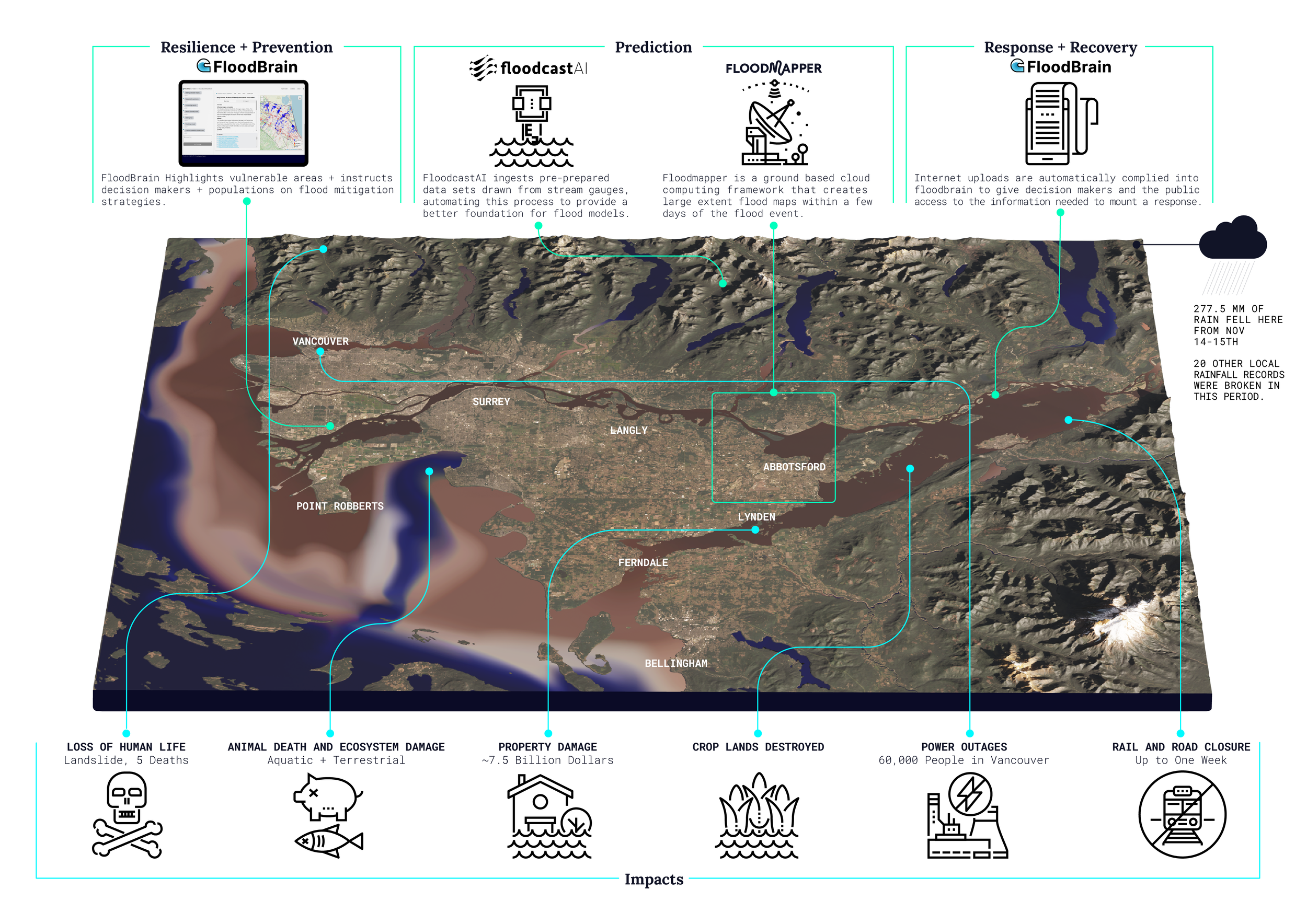

Floodmapper, Rapid ML derived flood maps at scale. floodmapper.ai

Visualization For Impact

AI doesn’t just have to be used for weather forecasting. It can be used to educate the general public about climate impact and resilience as well. “Using AI tools for visualization helps get the message across. With animation technology and 3D images based on real data, people get the message much more clearly that floods are actually very destructive, even if you’re not directly suffering from their consequences.”

Biggy Nguyen adds: “Floods are not as immediately perilous or devastating as an earthquake or hurricane. Sometimes, you have to wait months to see the full effects and the extent of the damage.” That’s where AI-generated visualizations can prove helpful to illustrate knock-on effects, like reduced crop yield.

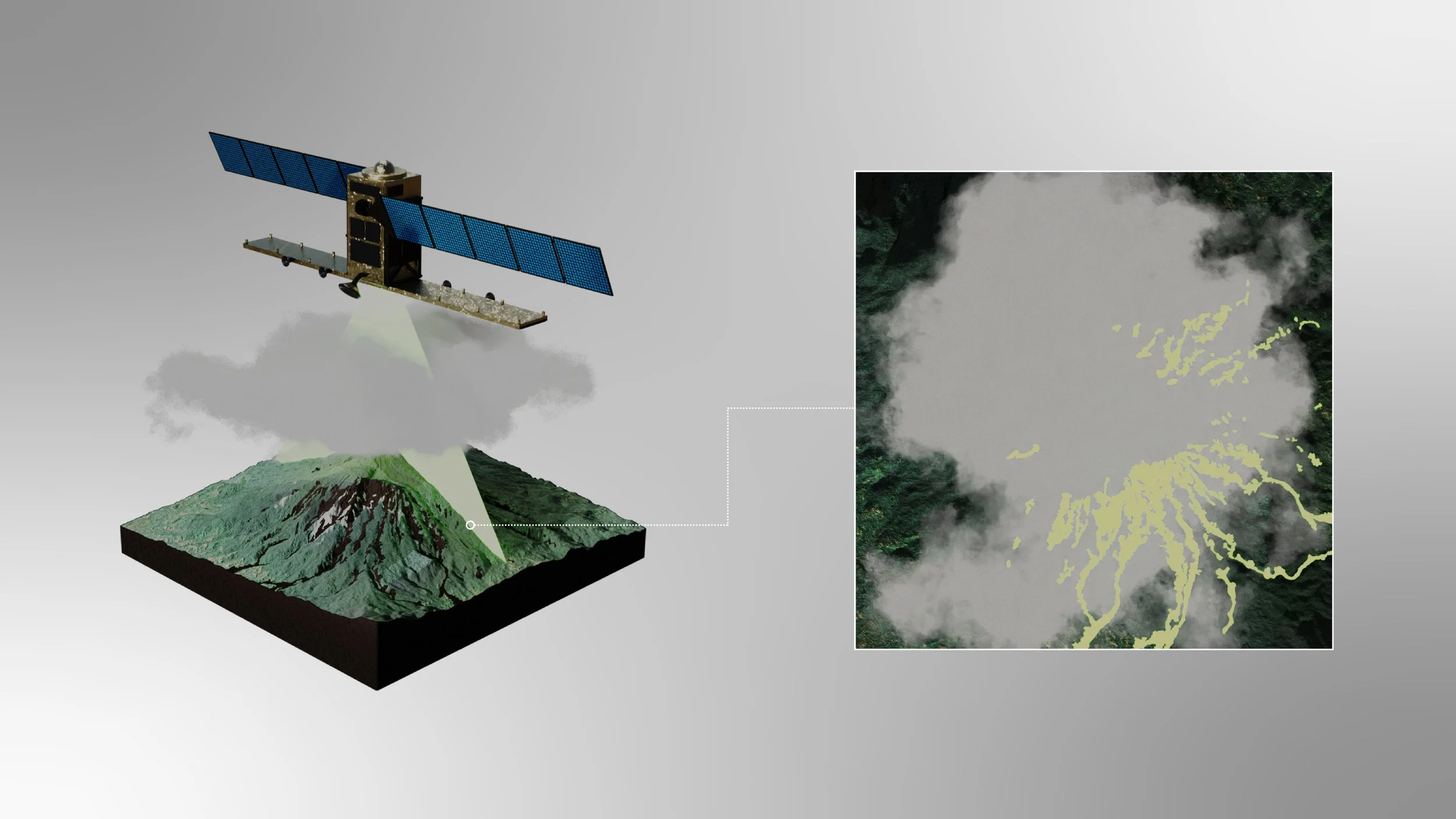

At the same time, many flood events are highly dynamic, meaning maps can become obsolete after just a few hours. The Frontier Development Lab’s WorldFloods machine learning payload demonstrated that flood-extent maps can be generated in space, directly on-board the satellites that acquire images of the Earth. The tiny-sized maps can be transmitted to the ground in a fraction of the time it would take to receive the images themselves.

“You don’t have to wait to get the data on the ground and then it’s 48-hours later and the maps are out of date. AI can help… this is a milestone. This is a breakthrough in satellite remote sensing of floods,” says Guy. “We’re in the age of New Space… It’s a wonderful thing. We should not try to stop AI, just make it better. Make sure it doesn’t do stupid things.”

AI Can Better Predict The Compound Effects of Disasters

We should wield caution, Guy urges, but also make room for optimism: AI for extreme weather prediction represents a massive opportunity to help us understand the complex interactions and knock-on effects that traditional forecasting cannot predict. An example can be found in the Tōhoku earthquake of 2011 in Japan, which caused a tsunami that led to the flooding of Fukushima Daiichi power plant’s nuclear reactors. This event was classified as a seven on the International Nuclear Event Scale — the same as the Chernobyl disaster of 1986.

AI models are able to calculate these complex interactions — not just how temperature change causes increased precipitation which leads to flooding, but how other seemingly-unrelated natural disasters and weather events can affect flooding — far better than humans.

Just as there are compounding effects that can affect flooding, the effects of flooding are also disparate and far-reaching. Typhoon-driven flooding in Thailand in 2011 severely disrupted automobile production, affecting supply chains on a global scale. People knew that they had issues finding cars, but they didn’t know that this shortage was due to flooding.

To model these compound causes and effects, collaboration is needed. “In the traditional world of academia, we don’t work together across fields. We push to, but it doesn’t happen. It doesn’t work,” says Guy. Collaboration is needed not just within academia but across sectors to include industry and government as well.

Électricité de France (EDF), an electric utility company, developed its own hydro-meteorological models to cover extreme weather like precipitation. These models pull data from over 1,000 stations in order to let EDF take preventative measures to protect the country’s energy infrastructure. EDF is a private company but the country of France retains majority ownership, representing a rare overlap of incentives and stakeholder needs between the public and private sector.

What would it look like for EDF’s flood system to be supported by machine learning models, or implemented broadly across the continent of Europe?

FloodBrain AI-powered flood report tool generated on-demand; deployed on Google Cloud. floodbrain.com

Flood-Proofing: A Vision For The Future, and How to Survive Today

What is the first thing you should do if a flood comes your way?

A. Get in your car and drive away

B. Pick up your kids from school and bring them home

C. Wade out of your house on foot for higher ground

D. Seek more information from the news or radio

Options A through C are appealing because they represent action, a sense of control over the urgency of a flooding situation. But flood waters can easily sweep vehicles off the road, schools tend to be safer than homes due to their established procedures, and wading out into flood waters puts you at risk of contact with contaminated water and downed power lines, which are an electrocution hazard.

Option D is the safest way to proceed, but in moments of stress, many people do not opt to sit still and wait. Decision-making under duress is faulty, and sees a bias towards the comfort of routine.

“I had a conversation with someone who got flooded,” Guy Schumann says. “He took his car out and opened the garage doors and the flood waters rushed in. Why did you even try? Why did you want to leave your house? He got in the car because that’s what he does every day.”

Even experts make the wrong judgment calls sometimes. Biggy Nguyen, who specialized in disaster resilience at Swiss Re, recalls an executive training activity. “As a team, we all had to survive an Australian wildfire. We were somewhere in the forest and we didn’t know where the wildfire was coming from. There was an option to stay in the cabin or jump in the pool. Some of us decided to try the pool — it turns out we would have been cooked in the wildfire. You would think the pool would be a good solution because of the water, but if a wildfire surrounds you, you are a pot on a stove being boiled.”

Given a lack of proper preparation, education, and procedure, we revert to our loudest instincts: pick up the kids, get out, get away. But often the most intuitive path is not the safest path forward.

Other natural disasters, like earthquakes, have clearly defined and well-understood protocols — seek shelter under a sturdy desk or doorframe, stay clear of windows and heavy furniture or appliances — as well as regular drills in affected areas. These guidelines don’t exist for floods in the same internationally-recognized and widely-disseminated way that is needed in order to save lives.

Should you get out of your car during a flood, or stay put?

Should you climb up to a windowless attic, or stay on a lower floor?

To be sure, gaps in knowledge and education exist across the spectrum of natural disasters. During wildfires, many people leave their air conditioning on, bringing smoke and polluted air directly into their homes. They may drive around barricades along evacuation routes, not understanding the jeopardy that may lay ahead.

According to James Parr, many don’t know that “during a hurricane or cyclone, your garage door is one of the weaknesses in your house. What happens is the garage door is the first thing to go, and it changes the pressure differential in the house and the roof pops off. The garage door is a place of weakness and no one thinks about how to make it the most robust.”

If you live in a flood-prone area, how can you protect yourself, your home, and your family?

Proactive measures include purchasing floodproofing materials like water barriers for your driveway and front door. These solutions can be expensive but they can also be as little as twenty dollars for water-activated flood barriers and sandless sandbags.

If you have a fuel tank in your basement for heating, ensure it is two-thirds full or more. If there is too much air in the tank, it can be de-anchored by water and float away. “In Luxembourg, we saw old tanks of fuel swimming down a river after a flood. But if they had been filled to the right level, they would have stayed,” says Guy. “You cannot expect everybody to know these things, but they can be communicated, because engineers know these things.”

During a flood, assess the situation. If you’re in a car, stay put, or climb onto the roof of the car if floodwaters rise. If you seek shelter in a windowless attic, you risk being stuck if the floodwaters reach you. Eliminate the risk of electrocution or fire in your home by turning off your utilities, like electricity and gas — except if your fuse box is in an already-flooded basement. Do not wade or drive into floodwaters, but if you do, leave your shoes on to avoid contact with bacteria, and do not approach wildlife like alligators and snakes.

Know that being on higher ground may not always help you. “If the drainage system or sewage system is under pressure, even if your house is aboveground and safe from outside flooding, that water can come in from underneath because of everything being under pressure,” says Guy. “And there’s actually an easy solution. There is a valve system that you can install, and when the system is under pressure, then at least the water doesn’t come up in your house. These are not expensive solutions and yet hardly anybody has them in vulnerable zones.”

AI Flood Technologies and Impacts

CREDIT: TRILLIUM TECHNOLOGIES

A Vision For the Future

“It’s probably a bit like the success of fire detectors in homes as a part of basic safety,” James says. “Unless it is mandated, people won’t do it.”

Individual education and awareness aside, the path forward for flood preparedness on a large scale may well come down to regulations, whether they be nationally-enforced flood drills or privately-enforced standards that incentivize flood protection with lower home insurance premiums.

“The first time I came to my flat in the U.K., I was like: what is my washing machine doing in my kitchen? Why isn’t it in the basement like everywhere else in Europe?” Guy says. In the U.K., washing machines are on higher levels to reduce the risk of electrification. The same risk is present for basement-level fuse boxes.

“So now there are electrical companies looking into this,” Guy says. “Going to houses that have been flooded and requesting that people move their fuse boxes up. And they cover the costs. People don’t need to cover the costs, they just need to let them in.”

The incentive is clear for electrical utility companies. Basement fuse boxes can malfunction during flooding, leading to higher repair costs and more service requests. Proactive measures like retroactively moving fuse boxes up a floor at no cost to the consumer can save money in the long term.

The public sector has a responsibility to enact proactive measures as well. Many countries, including Japan, have earthquake-resilient building codes. Other countries, like the U.K., have building standards which may not be uniformly enforced.

“In Luxembourg there are codes of how to build your building if it’s in a flood zone that the government recommends, but there is no law preventing you from building in that zone,” says Guy. “Take London: if you say, okay, now nobody build in a flood-vulnerable zone, you have to move the entire city and everyone in it… it’s not possible to move people, and people love to live near rivers, it’s natural… It’s wonderful except when it floods.”

One solution lies in purpose-built parks on waterfronts or flood plains that are meant to divert water away from homes and commercial buildings. “Playgrounds, can you make them floodable?” Guy asks. Cities like Copenhagen and New York City are doing so.

Floodable parks are a form of sustainable urban drainage systems (SUDS) that help communities and flood-prone areas grow more resilient to climate change.

There are also solutions like bioswales, which are troughs that act as drainage systems, diverting water away from homes and sewage systems. Porous rocks and permeable minerals in the ground also offer ways to mitigate flooding. China has commissioned “sponge city” concepts to aid its cities on flood plains, envisioning neighborhoods that are adaptive, resilient, and built for the future.

Across the ocean, the island of Kiribati is sinking as a result of rising sea levels, and will be underwater by the year 2100. “The former president gave TED Talks about Kiribati sinking year over year as part of climate change,” Biggy says, “And in response to that, some Japanese researchers have looked into building floatable islands where communities can live.”

These islands would be large enough to maintain 10,000 residents and 30,000 tourists. They would have medical facilities and laboratory space and operate self-sufficiently in terms of power, water, and food. These islands are designed with global warming and sea level changes in mind.

While an island that accommodates 10,000 residents is not a whole-scale solution, it is an example of the type of revolutionary thinking that is needed to build for the next generation. “We need to be bolder in our engineering missions,” says Biggy. “Instead of just retrofitting buildings, what can we do to make buildings more accommodating? How can we deal with this peril…instead of just living with it?”

Data Availability as a Barrier to Flood Resilience

How Are Floods Predicted?

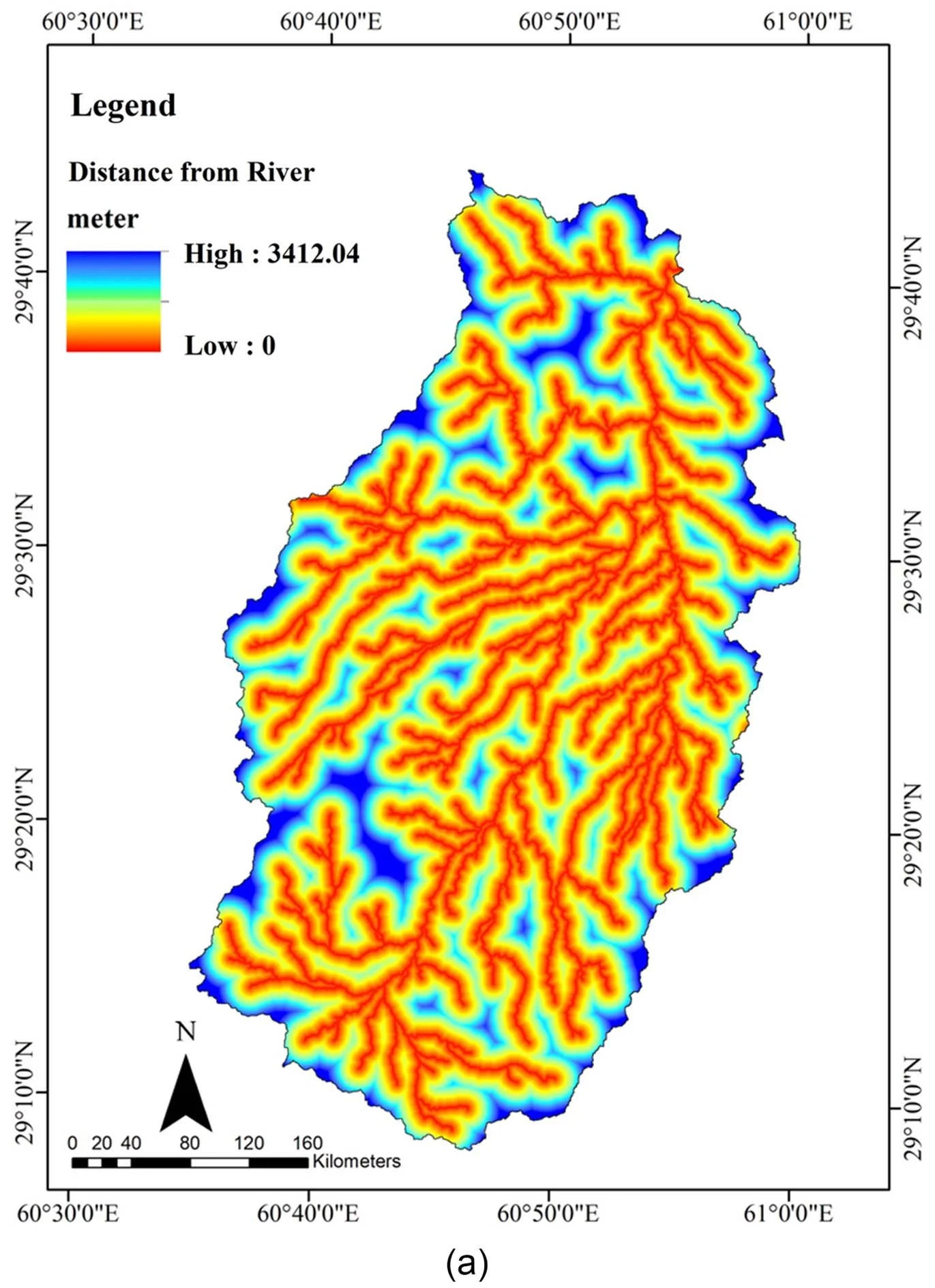

Flood analysis methods require inputs such as annual rainfall, rate of change in rivers, accurate storm tracking, digital terrain models (DTMs) and/or digital elevation models (DEMs), and knowledge of urban sewage system infrastructure, among other data points.

Credit: J Lloa / Pixabay

The task of unlocking this manifold data is often the first barrier to effective flood assessments and models.

“Just getting the input in order to generate an output is still a large challenge,” says Biggy.

Oftentimes, this data is simply not available, such as in developing countries without sufficient data measuring infrastructure. Other times, this data is siloed or withheld from certain audiences.

“When multinational companies try to do business with some governments and try to get ahold of weather data, that was very challenging because they basically barred you from access to any data, saying it’s a domestic security issue. And you would think it’s just rainwater in a particular area, but they’re thinking it might be harmful if people knew which areas were more vulnerable economically and ecologically.”

“That is understandable, in a way,” Guy says. “If you have a map of the vulnerable areas in a country, that is a useful piece of information if you want to use it” — for beneficial purposes in Swiss Re’s case, but also potentially for nefarious purposes if the data were to get into the wrong hands.

Biggy also recalls working on a project with a French multinational utility provider. “We were trying to address flooding and thinking that [the company] manages the sewage systems in most of the cities in the U.S. — we thought this was such a win-win. [The company] would bring the data and we could analyze the pumping systems and run the models. It turned out that [the company], although they maintain those sewage systems, didn’t know about their engineering conditions.”

The French multinational utility provider didn’t have access to the original plans from when different sewers were built. “They can give you an idea, but they can’t tell you about each turbine, how many tons of water it can process and pump in a particular hour… We talked with the city administration and they didn’t hold that information either because [the sewers] were built thirty years ago and no one held those details anymore.”

This is where projects initiated in good faith can run into roadblocks. “In a lot of conversations attempting to come up with solutions, it all actually stalls on data availability, especially when we talk about areas that were less planned, like Pakistan or Bangladesh, compared to traditionally planned cities like Paris.”

Data Inputs for Flood Prediction

Generally speaking, insurance companies need three types of data to conduct accurate flood assessments timely to when a flooding event happens: “The first question is always if we have satellite imagery on time and with the right accuracy. Then the hydrological models. Then we need to understand how high and how impactful the flood is.”

This last question, floodwater height, is answered using digital terrain models (DTMs).

“We use satellite imagery to measure DTMs — how much is really flooded, and where is the water going? If the flood is going downhill, the likelihood of water running into an area is much more impactful than if it was standing flat with nowhere to escape to… are we talking about thirty centimeters or three meters?”

For insurance purposes, and especially parametric insurance which offers payouts based on the severity of the event rather than its impact, insurance companies need to understand the peak water height, and how water moves across different terrains. DTMs, which map topographies in 3D, are the basis of this measurement. While DTMs can be generated from satellite imagery today, there is still work to be done to ensure satellite-derived data is as robust as it needs to be in order to generate more effective and representative flood assessments.

“The first time I was with the United Nations World Flood Programme (WFP) team, looking at the Mozambique flood, they had a few questions for me as a scientist,” Guy says.

“They brought in all the maps they received from universities and other institutions. One question was: which map should we use? And I asked: these different maps, are they all from different satellites? It turned out there were only two different satellites but there were fifteen different maps. If the world of mapping were perfect, you would see two different maps from fifteen different satellites.”

The fact that various flood mapping algorithms can produce fifteen different maps from the same data emphasizes the variability of AI model outputs when they have access to limited data points. In an ideal world, as Guy said, AI models would have exponentially more data and produce fewer, more accurate outputs.

Guy told UNWFP: “You should use all the maps and do an uncertainty analysis… But we don’t have time for that, because all the floods are going on at the same time everywhere.”

Universal Flood Benchmarks

Perhaps larger than the barrier of data availability is the crucial fact that there is not a unified flood scale or global consensus on what a strong mapping methodology or prediction model looks like in the scientific community today.

Hurricanes have the Saffir-Simpson severity scale of one to five; tornadoes use the Fujita scale of F-0 to F-5; earthquakes use the Richter scale; and volcanoes have an explosivity index of zero to eight. A parallel measurement does not exist in the world of floods.

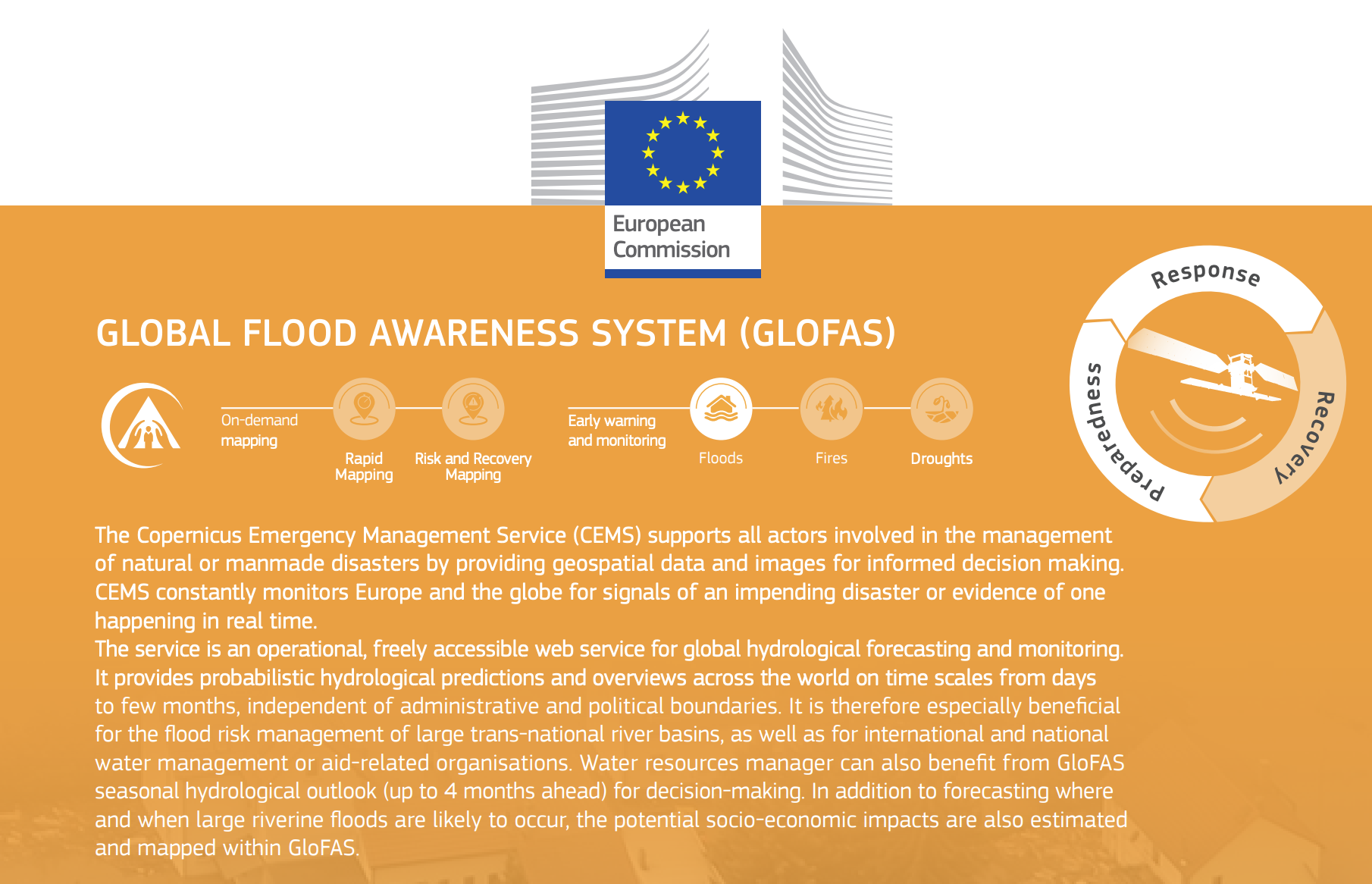

“Every nation is using their own model,” says Guy. “There is GloFAS, a global awareness model, but there’s no globally agreeable model for [measuring] floods.”

Global Flood Awareness System it is designed to support preparatory measures for flood events. https://www.globalfloods.eu/static/downloads/about/CopEMS_Poster_4.0_2021_GloFAS.pdf

The Global Flood Awareness System (GloFAS) has been forecasting and monitoring floods around the world since 2018 as a function of the European Commission’s Copernicus Emergency Management Service. It produces daily flood forecasts and monthly seasonal outlooks as well as real-time monitoring using satellite data.

Its data is free and openly available, representing a step forward in availability of data. It does not, however, provide real-time information on flash flood risks, coastal flooding, or already-inundated areas.

Looking Forward

AI presents solutions to the data gap in flood forecasting and monitoring. It can integrate available data sets with machine learning capabilities to infer outputs that pass reliability thresholds, as presented by Kim, et al. (2019), Mirkazemi, et al. (2023), and others.

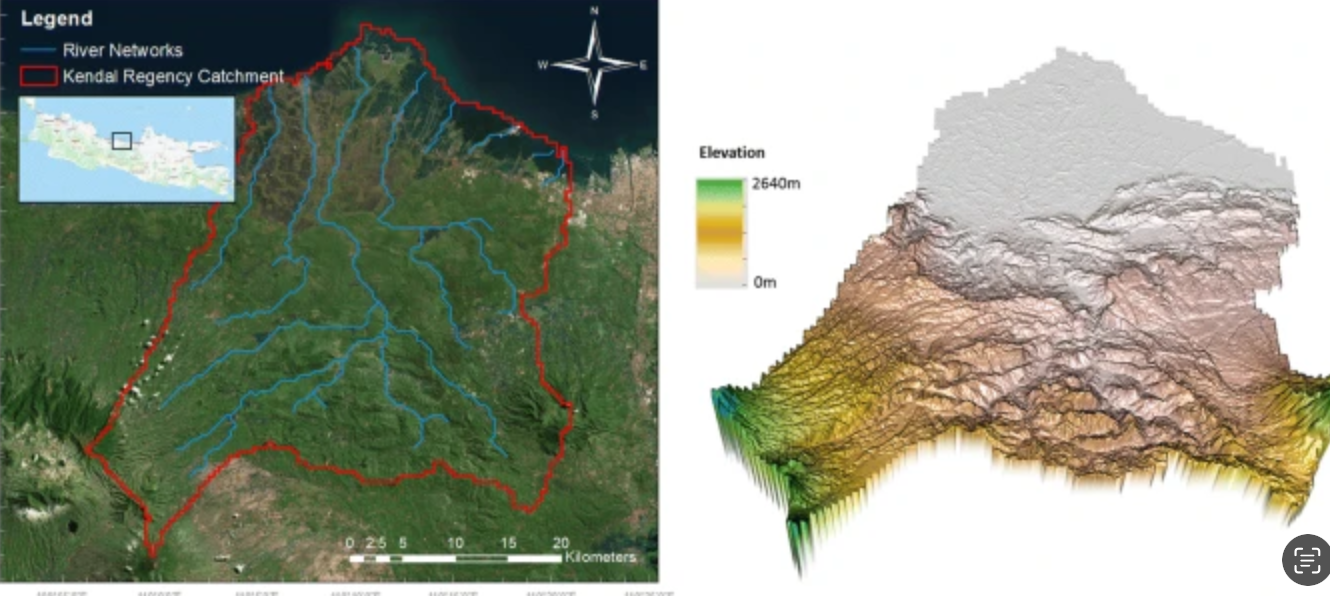

Using AI to improve flood assessments is an ongoing FDL initiative. “I was involved in that… the first challenge was to find the data that would feed the ML model. And that was only possible because the hydrological community came together the year before and created global data sets of hydrological measurements and parameters. If you use a global hydrological model with ML, it actually outperforms traditional hydrological catchment models.”

A catchment is an area that funnels water to a common path to form a river or creek, and catchment models aim to model these pathways.

During FDL 2022, data arrived just in time for Guy and his team to work on their flood resilience research. But even those global data sets are not perfect.

“I think the scientific community needed maybe twenty years of convincing to finally put out a common database of measurements and parameters, and, you know, some countries are not feeding their data to it.”

Open, large-scale data sets and increased data availability from satellites represent a step forward in painting a complete picture of flood activity. In the interim, that picture is more of a sketch.

“Even Swiss Re’s headquarters flooded in 2021,” Biggy says. “We’re talking about a risk management company, and some people were not prepared for that.”

Flood Mortality as a Social Crisis

Says a paper by Lindersson, et al. (2023) published in Nature Sustainability. The paper starts with an anecdote:

“‘When there is rain or snow, you can make more money’, explained a food-delivery worker who had been wading through knee-deep floodwater amid the extreme rainfall of Hurricane Ida in New York City. Despite New York being one of the richest cities in the world, many like him could not afford to miss even one shift. The storm caused a number of fatalities, particularly in illegal basement apartments, highlighting the intersection of poverty and inadequate housing conditions. Time and again, disasters expose existing inequalities in a ruthless way. We think that this is alarming since the gap between rich and poor is widening in many countries across the world, whilst climate change is also intensifying extreme rainfall patterns and, thus, increasing the magnitude of major flood events.”

This map displays 573 major flood disasters (dots) that occurred between 1990 and 2018, with the size of the dots indicating the number of reported flood fatalities, and the colour of the countries indicating their average level of income inequality across the sample. The flood disasters are reports from the Emergency Events Database (EM-DAT31) that have been georeferenced to districts (or smaller subdivisions) using the Geocoded Disasters dataset (GDIS)44. Basemap from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com/).

In this edition, we talked about urban areas purpose-built for flood resilience, expensive floating islands, and individual flood protection solutions for homes. But what about those vulnerable populations that lack basic infrastructure and resources, let alone disaster-ready infrastructure? What about those that are forced to live and remain in less desirable, more extreme weather-prone areas because of a lack of resources?

Gandhi, et al. (2022) found no evidence of population decline for cities in low-income countries that face repeat flooding.

Extreme weather deepens existing economic and social inequalities, and flood-related disasters have increased by 134% since the year 2000. In this way, flooding is a pressing social issue as much as it is a climate and humanitarian issue.

Avenues of Support for Flood-Prone Countries

“I was a bit mortified,” James Parr says. “We used FloodMapper to make maps of the Pakistan floods, and we couldn’t find anyone to give them to. When we talked to the United Nations, they said there is no one in Pakistan we really can give this to.”

When basic supplies like boats, funeral solutions, helicopters, and ambulatory services are urgently needed, countries may not be able to take full advantage of advanced AI mapping solutions like FloodMapper. “So I just want to shine light on that,” says James. “Making certain cities more resilient feels like it might be possible, but we still have billions of people who are massively vulnerable.”

When a government is concerned with emergency response measures, who do you go to with advanced, perhaps non-fundamental technological solutions?

Biggy Nguyen proposes targeting those with resources, and perhaps an innate sense of responsibility. “We have to broaden our own understanding of who we turn to. If you have flood maps of Pakistan, maybe you turn to the millionaires and billionaires in Pakistan rather than the government which is too busy grinding away.”

It is not unheard of for privately wealthy individuals to donate to disaster relief. In 2017, Kieu Hoang, a Vietnamese-American billionaire, donated $5 million to San Jose flood victims in California, increasing aid funds by sixfold.

In 2023, Hamdi Ulukaya, the Turkish founder of yogurt brand Chobani, pledged $2 million to relief efforts after the earthquake in Turkey earlier in the year. But individual generosity is not a reliable — or unlimited — source of aid. And the worst flooding events have an average cost of $4.6 billion — not million — per event. After its floods in 2022 and 2023, for example, Pakistan requested $8 billion to support its recovery efforts.

Neither private wealth nor government intervention represent a holistic answer to flood response, especially in developing and flood-prone nations.

And yet, on an international scale, the resources needed to support flood demands are present. “I wrote a letter to Obama,” Guy jokes. “Because the resources are there globally. We have enough to help people. We have enough technological advances. We have enough powerful resources available.

We have enough, but do we work together? Well, never really.”

“Do we have the resources?” Biggy says. “Yes and no. The world in general has the resources, yes, but the people deciding over those resources [are the roadblock]... When I was at Swiss Re, one of the products we were trying to lobby for was insurance for green infrastructure. Because when you talk to multilateral development banks like ADB and they want to channel private investments into needed infrastructure, investors are still skeptical.

Say if a project is delayed and you don’t get your return on investment immediately? Insurance can help.”

“And despite having these conversations at a high level, there is still something about people [not] wanting to embrace change when it is offered on a silver plate in front of them. It’s something I haven’t understood but I’ve come across so many times. We have solutions, we have the technology, we have the resources — mapping this all together is an issue of collaboration, but also of interest. Do interests always align in the exact same direction? Or is it more that we are generally looking towards the same future, but when you go into the details, it’s really not the same future.”

But despite failures of collaboration and alignment, funds do still make their way to some countries in need thanks to intergovernmental organizations (IGOs) like the World Bank. In 2022, the World Bank loaned $400 million to Indonesia in an effort to bolster the nation’s flood resilience programs;

“this program will serve as a national umbrella program to help coordinate sources of financing and function as a knowledge hub to help Indonesian cities leverage good practices and continuously advance sector policy, practice, and innovation.”

Money cannot protect against floods entirely, but it can safeguard against some of their worst effects, and proactive investments in infrastructure and early warning systems have the potential to speed up recovery timelines and mitigate further economic decline.

“The World Bank has been doing good work around building this national pool called SEADRIF (Southeast Asia Disaster Risk Insurance Facility) because these countries, although they are subject to floods and draughts, they don’t get attention and international aid towards these perils to help their communities deal with it or build resilience,” says Biggy.

Those That “Do”

Credit: Hitesh Choudhary/ Pexels

“In the end, it’s left to NGOs, [IGOs], or corporations. Conglomerates are very present in the Philippines… they say ‘we have the money, so let’s just pull it off ourselves… These are the kinds of things where maybe we rely too much on authorities because we feel that it’s part of their mandate, what they should do, but all those ‘shoulds’ don’t get us far quick enough. So maybe we should turn our heads towards those that do, without the official mandate.”

Biggy shares an example of a conglomerate of corporations in Manila that came together to create an earthquake risk management pool for the area surrounding a large mall that they were stakeholders in. “When we asked them: why would you do this humanitarian act? They said that people go to malls post-disasters because they have facilities, toilets, running water, and you’re kind of sheltered. And they want to keep the malls for people to go to — not just as an evacuation space. Their motives might not be the most noble, but in the end, at least they are trying to do something about it… Whereas the government has a lot of problems to pick from.”

“There are some things you can do to protect yourself at least a little bit against floods [as an individual],” Guy Schumann says. “And if you have support from a local community, it’s also possible to do that. I agree with the fact that we should not sit around and wait for governments to do something really fast and big, that we should go to the people that are already doing something on the ground. And this is very often NGOs… a lot of these NGOs are doing great things.

And a lot of rich people can do great things if they want to… we should look into these avenues a bit more, because getting something into policy and then politics and then government and then law and then action is a very lengthy process.”

Floods are multi-layered disasters with a host of short- and long-term effects; flood response measures, especially for vulnerable populations, will have to be similarly multi-layered, involving a variety of stakeholders with different responsibilities and specialties. The burden will likely need to be divided and carried by governments, NGOs, IGOs, individuals, and private corporations alike.

Lindersson, et al. suggest that policy aimed at closing the income gap can also act as a disaster-risk reduction method. “It enables risks across multiple hazards to be reduced simultaneously, that is, more unequal societies are not only more vulnerable to floods, but also to pandemics, droughts, and other disasters.”

FDL Europe’s SAR team developed a generalised tool for assessing disasters (such as floods and landslides) through clouds and at night.

CREDIT: FDLEUROPE.ORG / TRILLIUM TECHNOLOGIES

5 Implications

Floods are the world’s #1 climate issue — their prevalence and magnitude is increasing at a rapid pace due to rising temperatures, and we need to address their prediction, response, and resilience measures head on.

The “we” in Implication #1 is complicated. Governments, NGOs, IGOs, corporations, communities, and individuals can all make a difference, but the division of responsibility is a tricky process to get right — especially when certain nations are already vulnerable and under-resourced.

The “how” is complicated as well, but AI provides a promising pathway forward in terms of flood mapping, prediction, and visualization. It has the capacity to understand the compound effects of flooding in a way that traditional forecasting cannot.

The availability of data both on-earth and in-orbit will be a hurdle towards AI capabilities reaching their potential, though some ML models are already showing promise in inferring outputs that pass reliability thresholds.

Zooming in, floods are endemic to all parts of the world that experience rain, but individuals in these regions often do not receive basic education on how to shield themselves from flooding’s worst effects, and behave during a flooding effect. More education and individual resourcing is needed in this regard.

5 Actions

Floods are the world’s #1 climate issue — their prevalence and magnitude is increasing at a rapid pace due to rising temperatures, and we need to address their prediction, response, and resilience measures head on.

The “we” in Implication #1 is complicated. Governments, NGOs, IGOs, corporations, communities, and individuals can all make a difference, but the division of responsibility is a tricky process to get right — especially when certain nations are already vulnerable and under-resourced.

The “how” is complicated as well, but AI provides a promising pathway forward in terms of flood mapping, prediction, and visualization. It has the capacity to understand the compound effects of flooding in a way that traditional forecasting cannot.

The availability of data both on-earth and in-orbit will be a hurdle towards AI capabilities reaching their potential, though some ML models are already showing promise in inferring outputs that pass reliability thresholds.

Zooming in, floods are endemic to all parts of the world that experience rain, but individuals in these regions often do not receive basic education on how to shield themselves from flooding’s worst effects, and behave during a flooding effect. More education and individual resourcing is needed in this regard.

About Intelligence Age

After the information age comes the Intelligence Age, when artificial intelligence will enable technology on Earth and in outer space to not only be infinitely connected, but in conversation with itself.

Let’s join the conversation.

Intelligence Age is published multiple times a year by Trillium Technologies. Each edition features a discussion between today’s AI and space leaders about tomorrow’s most pressing problems and most promising ideas, from AI safety and ethics to inter-planetary stewardship.

About Trillium Applied

Trillium Technologies has over a decade of experience providing professional consulting services to leading global organizations from Nike to NASA, the U.S. Department of Energy to British Telecom.

Trillium Applied is our dedicated consulting and applied AI service. We blend world-class, PhD-level research depth with the speed and agility of a modern organization to tackle your biggest problems today, not tomorrow.

Work with us to create and deploy trailblazing applied AI. Learn more and get in touch at trillium.tech/applied.